Pok owned a large farm where he raised cows, pigs, water buffalo, chickens, ducks and lots of fish in a pond. The family hid their gold in a clay pot, buried where the banana tree grew. It was well known that people in Koas Krala had lots of secreted gold, and the name of the town signifies that.

Mao was my parents’ firstborn child. I called her mean Mao because she always wore a stern expression. Cina was the pretty one, and then came Pech, and I was the youngest. My name is Chanra. My father’s daughters from his first wife were Seam, Poey and Tha. They were all married. Seam and Poey lived with their husbands in the nearby city of Battambang. Tha was my favorite sister, a striking and stylish girl. She carried me everywhere until I got too heavy. I followed my sisters to school at the nearby Koas Krala temple, where the monks taught reading and writing. I enjoyed the lessons, mostly because the monks fascinated me with their shaved heads and eyebrows, and their wrap-around saffron robes, especially the youngest monks arrayed in the brightest color. They wore nothing underneath, but I did not know it at the time.

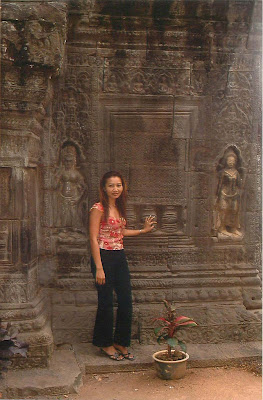

The temple was made of stone, fit for the Gods, and sat regally in the center of town, facing east. It was enclosed by a wall, next to a tranquil pond crowded with floating lilies. Sculptures of many-headed cobras, or Naga, adorned the balustrades of the pathway leading to the shrine. Its three levels formed a pyramid shape, like a temple mountain. The steep stairs on the tiered base led up to the terrace with an open pavilion, galleries and library, and on top of that perched the central tower. The tall pointed roof looked like a crown with five peaks, one at each compass point and one in the center, topped with a domed cupola. The exterior walls were intricately carved with bas-reliefs of battle marches that showed the coming of the French. They were studded with sculptured columns, each one different from the next.

On a warm day, I looked up at our temple with pride. I felt humbled by its size as I stood in the dappled patches of shade cast by tall mahogany trees growing just outside of the retaining wall. I wore shorts, thong sandals and little else. Vendors sold fruits and vegetables nearby, and the smell of sweet rice dumplings tempted me. I ran to the stairs, and then up and down, and then back up to the railing of the terrace, which was rough in my hands. I made my way around and around the patio, and then through the gilded doorway to the central sanctuary. It was dark, but I could still see the paintings on the walls depicting the life of Buddha one side, and on the other a parade of costumed men and women riding harnessed elephants draped in ceremonial colors. Huge stone figures stood sentinal on each side of the room, and I sought comfort in the half-closed eyes and gentle smiles of those meditating Buddhas. Behind one of them I discovered the perfect hiding place. I crouched there, just as quiet as a statue, concealed and waiting. When my sisters finally came up from the library to find me, I seized just the right moment to jump out, shouting and laughing and shattering the silence. Then I ran back out, down the stairs, and all the way home, just ahead of everyone else, to be the first to claim the rights to the big hammock, the one that Mai had made from coconut fibers, that was hanging in the shade underneath our house on stilts.

Everyone gathered there; my family, our neighbors, friends, aunts and uncles, grandparents, and anyone with a song to sing or a story to tell. My Uncle Jem was a Captain in Lon Nol’s army. He visited us, and told stories about his military expeditions and the fighting in other parts of the country. The war seemed so far away then.

I preferred to lose myself in the traditional Cambodian music we listened to. It was under the house that I first saw the boy, Nary, playing the khim. He came from a nearby village, wearing a big straw hat, and he rode in on a bicycle with a basket on the back that held the wood and brass khim. It was an elegant instrument for such a boy. He played while sitting with his legs crossed, striking the bronze wires with rubber-tipped bamboo rods. The women danced. I played finger cymbals, called chhing, and watched Nary intently as his lips moved to the music, but he did not sing. He looked happy when he played, even when the songs evoked sadness.

We listened to plays broadcast from Phnom Penh on the radio. One told the legend of the beginning of the Kingdom of Cambodia. A beautiful Khmer Princess met an Indian Brahman, as they both sailed through the watery land. He fell in love at first sight. The Brahman shot an arrow from his magic bow into her boat and she agreed to marry him. Many of the folk stories were tragic, and left me wishing for a happy ending. I favored princess fairy-tales; one in particular about a young lady with many suitors, all trying to marry her for her money. The clever girl lured the men into a room full of her jewels. When each of them stepped up to take one of the valuables, he dropped into a hidden pit of warm mud and sticky rice. That test revealed the greed of the deceitful men. The Princess then married for love.

Springtime was always my favorite time of year, when the dry heat came on and we celebrated the New Year. I would wake up at dawn when it was still cool and quiet, and slip noiselessly out of bed and tiptoe past my sleeping sisters, and very stealthily, skipping the floorboards that creaked, make my way to the kitchen. My breakfast was always a feast of the leftover rice stuck to the bottom of the pot, with lots of soy sauce. Then I would peek outside and take a deep breath of the fragrant early morning air, and look to see if our horse named Samnang, which means lucky, was waiting for me at the bottom of the stairs. If I came out with a special treat, he shook his mane and bent his head down so I could pet the white star on his forehead.

The barefoot monks came by, chanting their prayers and collecting alms. It was an honor for me to give them food. I made my own rounds of the neighborhood. Next door, I watched the cleaning and pounding of massive amounts of fish, and the preparation of the prahok fish paste. I ran barefoot in the rice paddies, skipping my way down the low earthen dikes that divided the fields into square patterns, where rice grew taller than I was. I usually arrived home dirty and smelling of fish. I played by our pond, under the shade of the fanlike fronds of the sugar palm trees. My sister Tha’s husband helped us get the sugar palm juice, an important job before our social gatherings. He scaled the tall, slender, curving tree trunks with a ladder, to gather nectar from the flowers by letting the juice drip through a bamboo pole and into a jar. By morning the jar would be full of the intoxicating juice.

I had everything, even a new baby brother. Srey was born, chubby and adorable. Mai was so happy; finally a boy. For whatever reason, her other sons had died; one miscarriage, and another at birth. To ensure that the spirits would not take Srey, Mai dressed him up as a girl. He wore an earring and a dress for the first two years of his life, and became part of our contented family.

We ate our dinner together after Pok came home from work. He often went to Battambang City for business. I secretly knew that he loved me the most, because without fail, he returned with a bag full of fancy hard candies. He always gave it to me.

"One piece for everyone…and the rest are all mine!" I announced.

I did not want to share, especially the green and white ones, which were sweet, and they never spoiled my appetite.

Mai made the savory B’baw Mouan soup with chicken and rice in a hot pot, the aroma filling the kitchen. I set the table, putting all the food out at the same time in various bowls and platters; with small bowls of fish sauce, soy sauce, salt and pepper, lime slices and chilies.

We were preparing for just such a meal when I first heard the sounds of war in our village. It was June 6th, my eleventh birthday, not a big celebration, but Mai always remembered. Suddenly, loud booming sounds resonated from somewhere off in the distance.

"What is it?" I asked.

I could tell by the look on Mai's face that something was wrong.

"Chanra, call for your sisters, we must go," she said in a strangely calm voice.

"Where, Mai? And where is Pok?"

"Pok is waiting for us."

Mai packed up the food in a basket that she placed in my arms. She steered me to the door and down the stairs. She carried a rolled-up floor mat, a blanket, and Srey in his little dress. Again I heard a loud noise that sounded like thunder. My sisters Cina, Pech, and mean Mao were already coming in from the fields, followed by the horse Samnang. They tied him up under the house as he snorted and stomped his feet. Mai prodded me along as we headed toward the temple. My sisters ran to catch up with us. Usually Mai told us to be quiet when we walked, but she did not seem to notice our loudly clicking thongs. That worried me.

"Pok, Pok!" I called when we got to the entrance of the temple.

My father and some of the other men from town were putting palm fronds and tree branches up against the inside of the surrounding walls, tying them together with vines and barbed wire. Pok waved us under the cover, and I saw some of our neighbors there too. We all sat down, huddled closely together, and for a while heard nothing but the sounds of our own heavy breathing and the low voices of the men keeping watch outside.

And there it was again, still far away, but unmistakable, the sound of explosions. Mean Mao said they were bombs, Cina said they were missiles. Srey cried.

"Have some birthday rice cakes," said Mai, trying to distract us.

We each took one from the basket. I took one more. We sat on the floor mat, wrapped up in the blanket, in the dark, until at last we fell asleep.

The sun shone brightly when we awoke, and Pok said we could go back home. Everything seemed the same as always when we got back to the house. Mai made a pot of jasmine rice. She set aside enough for our lunch, and then prepared another portion with slices of jackfruit, which she stuck with sticks of incense and placed on the altar. I picked some wildflowers growing in the yard and laid them next to the offering. Mai lit the incense and got down on her knees, put her hands together out in front of her, and bowed her head three times. Together we prayed to the spirits of our ancestors.

Pok went back to work on the shelter, and everyone else did chores as usual. Srey and I watched Mai in the kitchen. I noticed the crease between her eyes that told me she was unhappy. I tried to be helpful and ladylike because she liked that, and she did not have to tell me once not to talk too much.

The warfare that was once just part of Uncle Jem’s military tales had reached the outskirts of our village. The communist fighters were called Khmer Rouge. They wore all-black outfits, with red scarves so bright we could see them lurking by the edge of the nearby jungle. Sometimes they would come into the village looking for one particular person. We heard that a man was taken away, an artist. The soldiers said they needed him for a special job. Pok suspected that it was because he was of Chinese descent. We started spending most nights in the shelter, along with the other villagers. When darkness fell, the sounds of gunfire always seemed a bit closer. Mai told me to imagine that we were playing hide-and-seek in my favorite place. But I suddenly felt too old for that, and the grand Koas Krala temple was different too. The shelter stretched out along the inside of the surrounding wall like a train, each family had their own space. The men had strengthened the refuge by covering it with a mixture of mud and hay, and a layer of bamboo, thorny branches and barbed wire.

When we emerged from the shelter early in the morning, I always pretended that everything was fine.

"You are all lucky I got you into the hiding place, or you would be dead," I said merrily, skipping along. "And do not worry about farming because I did all of your work while you were sleeping!"

My family always pretended to believe me.

One day, as I jumped over a yellow ribbon in front of our house, I saw Tha and her husband riding up in one of Pok’s wagons, pulled along by two lazy water buffalo, kicking up dust from the dirt road as they approached. I dropped the ribbon and ran out to meet them. I did not notice the soldiers coming from the other side until they were very close to the wagon, and stopping it. They carried guns over their shoulders. Their black uniforms looked just like pajamas. The boys appeared to be young, not much older than myself, and I thought I recognized one of them as a peasant from a nearby village who had gone to the hills.

The tallest boy, with his red scarf wrapped around his head, called out to Tha and her husband, "Can you show me the way to the next town?"

Tha’s husband pointed in the right direction.

"Get down from the wagon and show us," the boy ordered.

I had never heard a young person address someone older so impolitely. Tha’s husband was a doctor; well educated and respected. Tha bravely threw her shoulders back, took her husband’s hand and headed off with him, followed by the boy soldiers.

I waited on the stairs of our house all day for their return, my eyes fixed on the road. I liked Tha's husband because he was always so patient with me, taking the time to give me water buffalo rides, steering me around the yard in circles. I waited some more. Mai told me not to worry, but the fact that she was praying did not reassure me.

Just before dark, I spied Tha returning, looking very small in the distance and bent over like she was carrying a heavy load. She came back alone. I ran to her, and when I put my arm through hers she was shaking.

"He is gone from this earth," was all that she could say.

That night in the shelter I asked about death. Mai told us what the Buddha said to his disciple Ananda.

"When they die, nothing will remain of them but their good thoughts, their righteous acts, and the bliss that proceeds from truth and righteousness. As rivers must at last reach the distant main, so their minds will be reborn in higher states of existence and continue to press on to their ultimate goal, which is the ocean of truth, the eternal peace of Nirvana."

Her words and the sound of her voice comforted me. But I felt sad because I knew that Tha’s husband would never return.